What I’ve learnt about storytelling from Mia Hansen-Løve’s films

One Fine Morning, a film by Mia Hansen-Løve (film still)

Since last year, when I finally watched Bergman Island after finishing a draft of my novel, I have become kind of obsessed by Mia Hansen-Løve’s films. After watching Bergman Island, I went on to watch Things to Come, Goodbye First Love and most recently One Fine Morning.

What I love so much about all these films, and about Mia Hansen-Løve and the way she writes and directs, is that they are so understated, and so beautiful in terms of aesthetics and cinematography but also in subject matter and in the very writing, the dialogue. And with this understated quality comes simplicity, clarity. If people love each other, they just say it. If they hate each other, they say it too. There’s no unnecessary build up, no unnecessary back story. We live in the moment, with all of these characters who feel real because they are complicated and hold all sorts of conflicting emotions all at once. All of these films share a quality of bittersweetness and delicacy that I just love.

I keep a notebook, in which I write down all my thoughts after a certain film or book or even television show has moved or inspired me. I have tons of notes on each of these films and I could write a blog post on each, and indeed perhaps one day I will (I still have a few more films in her back catalogue to go!).

But for now I wanted to share what I’ve learnt, and what I think I’ll continue to learn, about storytelling from Mia Hansen-Løve’s films, or at least the four that I’ve watched so far.

Bergman Island, a film by Mia Hansen-Løve (film still)

It’s okay to write about the same theme, again and again

In Bergman Island, the character Chris, a filmmaker, starts writing a film (there’s a film within a film) about a New Yorker who travels to Faro for a friend’s wedding where she reconnects with a significant old flame. And there’s lots of old flames in these films. In Goodbye First Love, for instance, a teenage couple, Camille and Sullivan, meet again eight years later; in Things to Come, Nathalie (played beautifully by Isabelle Huppert) rekindles a platonic relationship with a favourite former student; in One Fine Morning, Sandra bumps into an old friend Clement in the park, only for them to then embark on an affair.

I love that this theme of someone from the past reappearing in the present recurs again and again, but it never feels gimmicky. Each film is still individual, but the commonality threads them together, kind of like short stories in a collection. I love that Mia Hansen-Løve is unapologetic about returning to the same themes again and again; love, relationships breaking up, meeting the wrong people at the wrong time, rethinking the past, memories, families, fathers and daughters, mothers and daughters.

There’s a saying about how writers are always telling the same story, and maybe that’s not such a bad thing, to return to the themes that interest us to the point of obsession; it doesn’t mean the plot is always going to be the same or predictable, it just means each story, each film, is giving us a different perspective.

Mia Hansen-Løve references this quite directly in Bergman Island, when Chris says:

‘I thought we spent our whole lives saying the same thing.’

And Tim Roth, who plays her husband Tony, says:

‘We do, but from different perspectives.’

As an aside, I love this particular theme of someone from a character’s past reappearing in the narrative, indeed it’s a theme that I explore quite a lot in my own short story Premonition, when a young woman encounters her teenage crush, resulting in this moment of introspection and confusion as she tries to understand her feelings about him. Bringing someone from the past back into the present raises all sorts of thoughtful questions about how much people change, whether we really do, because mostly we revert back to the way we used to be with them. And this is again a big theme of Mia Hansen-Løve’s films, which they each explore beautifully.

Things to Come, a film by Mia Hansen-Løve (film still)

It’s okay to be inspired by your own life but to also not make that the defining feature of your writing

In interviews, Mia Hansen-Løve describes her films as fiction but also admits that they are a little semi-biographical, and that there’s a confusion between fiction and reality and a blurring of boundaries. For instance, her philosophy professor parents’ divorce inspired Things to Come, she’s spoken of her own love life inspiring Goodbye First Love, and seven years ago, Mia Hansen-Løve herself went to write on Faro, like Chris in Bergman Island does. In One Fine Morning, the lead character Sandra deals with her father’s declining health; Mia Hansen-Løve’s own father died during the pandemic, and she has said in interviews that Georg, Sandra’s father, was based on her own father too. But of course, none of this means that she’s her own characters or would respond in the same way that they do.

I feel strangely conflicted over whether writers need to say if something is or isn’t based on real life. On the one hand, I firmly believe it doesn’t matter if it is or isn’t and I feel strongly that women writers aren’t necessarily given credit for their ability to tell a fictional story (I recall a press review for my collection Things We Do Not Tell The People We Love, which assumed that I was each of my characters from every story). On the other hand, I wonder sometimes if it’s disingenuous to claim to never take inspiration from real life (because I do, at times, and probably more often than not without me even knowing it).

Anyway all of this to say, I like the way Mia Hansen-Løve approaches it:

Each of my films are like diaries of my life. Not that they are all autobiographical—I don’t mean it in that way—but my films are companions for me. I’m trying with my film to understand life better. I’m in a constant quest.

(In this interview)

Filmmakers are not their films, in the same way that writers are not their books. But I think it’s entirely likely and possible that our work captures something of how we might have felt at that time in her life when we happened to be writing that piece of work. I can see it in my own writing too; at the time that I wrote Things We Do Not Tell The People We Love, I was surprised at the darkness, the sadness and melancholy but now, reflecting on the time of my life that I was writing those stories, it doesn’t surprise me at all. So even though I might not be my characters, the feeling, tone and atmosphere of those stories reflect a piece of me emotionally. And that doesn’t take away from the craft. And that’s okay.

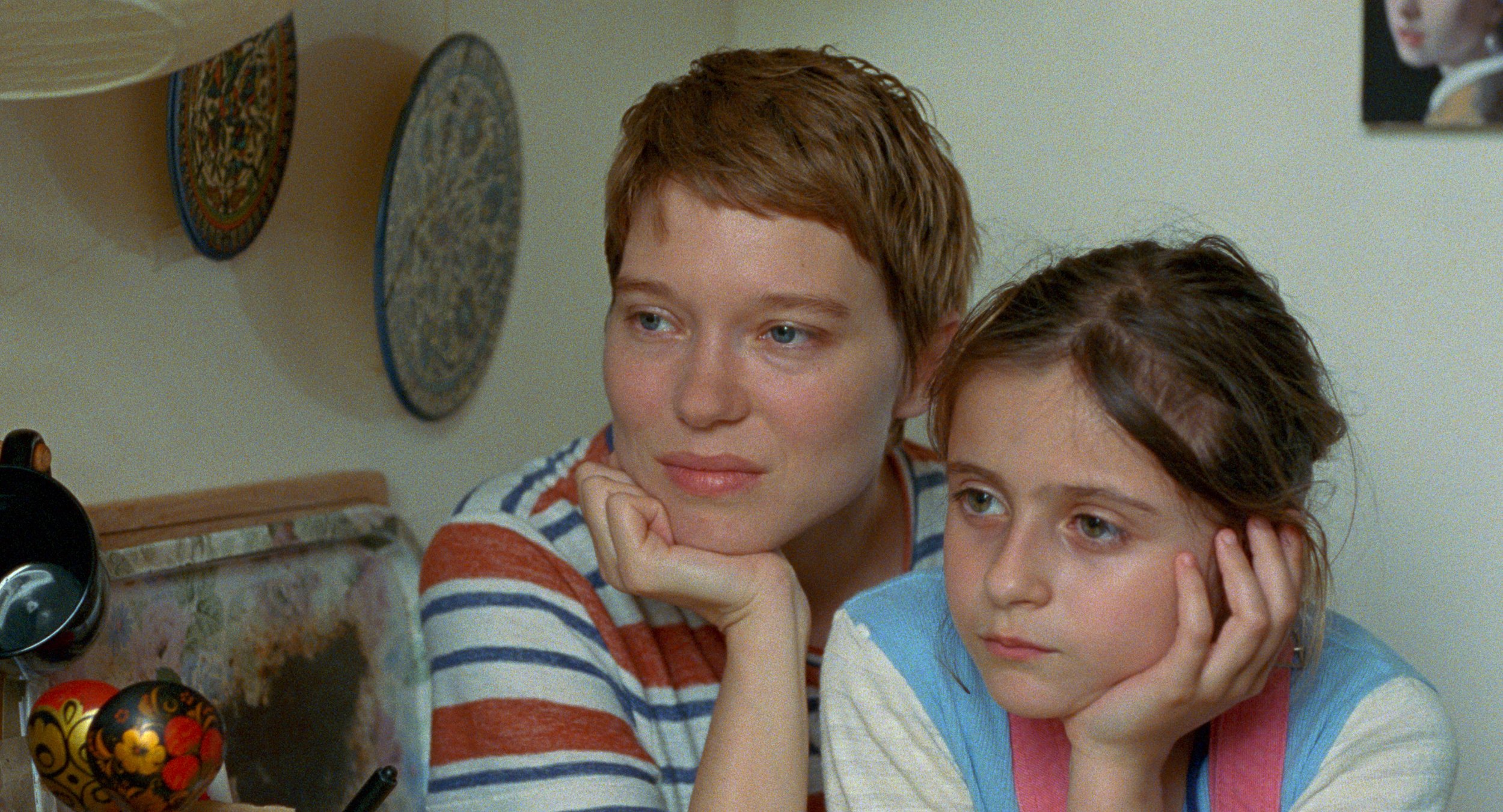

Goodbye First Love, a film by Mia Hansen-Løve (film still)

You don’t have to explain everything to your audience

In Bergman Island, when the film within the film starts to play, it’s not announced in anyway; as a spectator, you just have to figure it out. Similarly, in Goodbye First Love, we jump forward eight years, but there’s no big announcement; it just moves on, time just moves on, the way it does (we figure it out because Camille has shorter hair and we learn that she’s now a student of architecture.) In Things to Come, there’s a divorce, but it’s not drawn out, we don’t see scenes of legal battles in the way that we would in, say, a television series. Instead, it all happens off scene. In One Fine Morning, I found it so interesting that there’s hardly anything drawn out about Sandra’s feelings towards Clement; their relationship simply starts with a kiss, very, very quickly. We simply move forward in time without having everything explained, every step of the way.

I love this way of writing and storytelling, and it’s the way I try to write and it’s what I try to hold onto. For me, this way of storytelling keeps the focus on the emotions, the heart of the story, rather than filling in the facts of back story to make it more believable (but would also make it less compelling).

In my notebook, I’ve underlined this quote from Mia Hansen-Løve in this interview:

There are two very opposite ways of withholding information. One way is about creating suspense but ultimately delivering information that is nothing more than information. The other way is to make life bigger than cinema. Which is as it should be. Telling a story is about holding back information, but it can have the total opposite meaning, and for the opposite reasons.

Which is a rather wonderful way of putting it.

Bergman Island, a film by Mia Hansen-Løve (film still)

Settings are just as important as characters

In Bergman Island, the island itself becomes a character, its wild unspoilt landscape becoming the backdrop for the moment that reality and fiction begin to blur, as the film within a film begins. Watching it, I was struck by the clarity of the light, the water, the whispering of the sea and the long, soft shadows. There’s this real sense of being transported, just like the characters are, to somewhere so far away and remote. And it’s here that Chris is able to write, and finally break through the writing she’s been struggling with.

Similarly, in Goodbye First Love, Camille and Sullivan spend one last summer together in Camille’s family’s summer house in the countryside. They are there, just the two of them, and you get the distinct feeling that they are playing at being grown ups in this beautiful stone house. It’s such a gorgeous setting, almost so gorgeous that it’s inevitable that their relationship will crack; but you also can’t escape the feeling that this is where Camille belongs, more than Sullivan who is (perhaps fittingly) itching to travel and see the world. And it feels significant that Camille returns to the countryside at the very end, swimming in the water again.

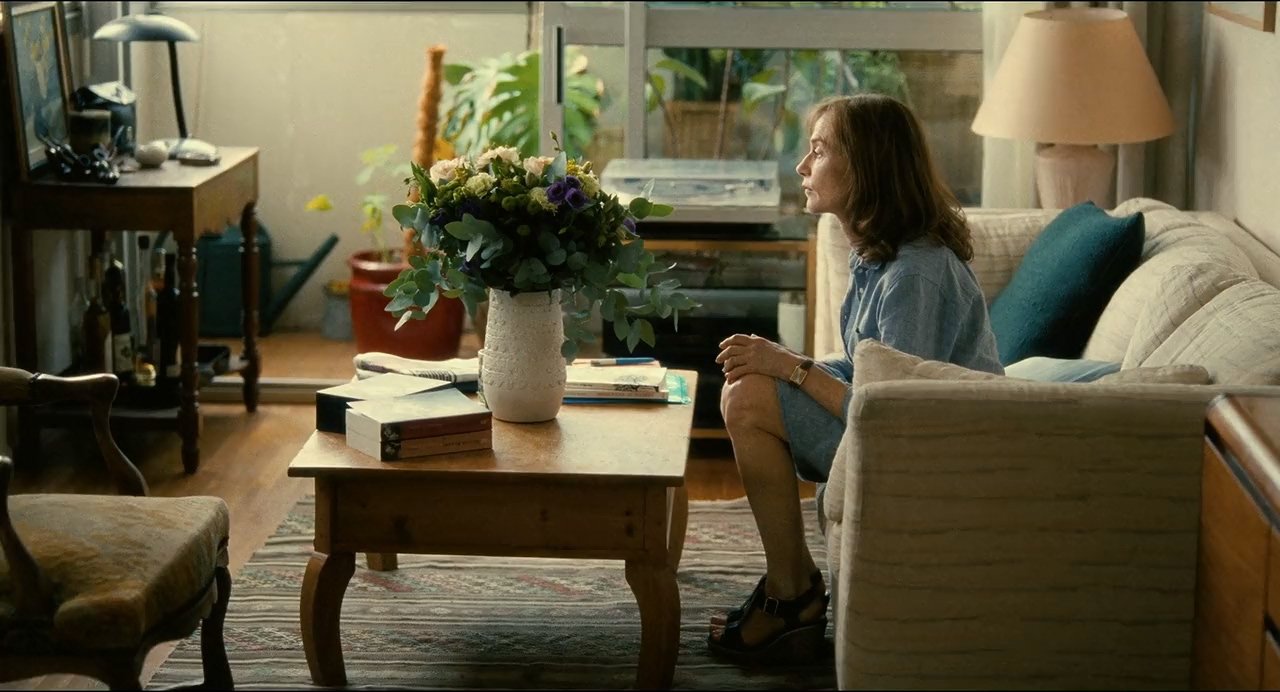

Things to Come, a film by Mia Hansen-Løve (film still)

And then there’s those beautiful book filled Parisian apartments in Things to Come and One Fine Morning; again, in Things to Come, Natalie escapes to the countryside while her husband moves out, but in this instance, it’s not at all really where she belongs and it makes sense that the film ends with her back in her Parisian apartment. And in One Fine Morning, Sandra moves between her tiny apartment, which she shares with her daughter, and her father’s apartment, and care homes, and hospitals, until at the very end, she stands at the top of Montmartre and is finally able to take in the view, take in the city where she lives (because in a way, she’d kind of stopped living before Clement). Though her life is still complicated, she stands there with Clement and her daughter by her side, and there is a sense that perhaps she won’t be as lonely as she was before.

Obviously this visual texture is something that translates in filmmaking but I don’t think it’s impossible to capture this in prose either; there’s a place for setting and description, when it enhances everything else around it, and I think, in writing, the sense of setting only adds to the intimacy of a character’s life, as well as reflecting something of a mood, a feeling. It seems necessary to place characters in a world that feels textured and real, and setting can do that.

Besides, I’m obsessed by stories that take people away from their usual everyday environments (as happens in pretty much each of the films mentioned) and place them far away. Away from home, tensions explode, anxieties heighten, people are out of sorts, refuse to play the same roles that they usually play when they’re in their normal surroundings. A lot of my short stories in Things We Do Not Tell The People We Love were set around this premise of dislocation, discombobulation. Because away from home, things happen. Dangerous things, exciting things, unexpected things. In so many of these films, we move from location to location, which keeps the story moving, both in terms of character and place.

One Fine Morning, a film by Mia Hansen-Løve (film still)

Music as inspiration

In this interview, Mia Hansen-Løve says:

When I write a film, I usually have up to four songs in mind from the start. These songs are with me during the whole process and sometimes even during shooting and editing. It’s a problem, actually, because usually when I end up using them in the film I’ve listened to them so many times that I start to hate them! The music never ends up there by accident. They give me some kind of direction or reassurance. It’s part of the inner world of the film.

I love this! And though a film can have a soundtrack in a more obvious way, there’s also no reason why a novel can’t. I almost always have a playlist put together full of songs that remind me of a certain time or mood or feeling, that help me with writing or editing or in between times when I’m not writing but I feel this pull to stay connected to the world I’m creating.

And that brings me to the end of this blog post! I hope you’ve enjoyed it, and that it might inspire you to watch any of these films (if you do, let me know how you’ve enjoyed them) and that I hope it shows as well that storytelling in all its kinds feeds into writing, and there’s so much to learn from so many artistic forms.

Miniature Worlds: a short story writing course

If you’d like to learn more about the craft of storytelling, you might enjoy Miniature Worlds, my short story writing course.

‘This is the most intimate writing course I have ever taken. I feel so held and you have been so generous with what you know.’ (Student testimonial)